Schools taking steps to reduce heat stress on students as temperatures continue to rise In Jamaica and the Caribbean

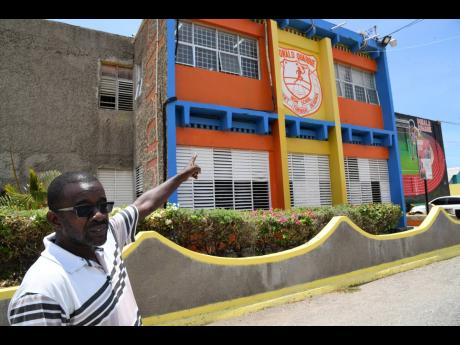

An occasional whiff of breeze from the nearby sea does little to ease the sweltering heat that blankets the Donald Quarrie High School in east Kingston. With almost no trees to provide shelter from the sun’s onslaught, the institution, built in the 1970s, depends on its louvre windows and ceiling fans in some of its classrooms to provide some relief.

But as global temperatures continue to rise, vice principal Patrick Williams acknowledges that this might not be enough, and is concerned about the impact the extreme heat will have on students’ learning and behaviour when the new school year starts tomorrow.

“The heat is terrible!” he declared, while leading The Sunday Gleaner on a tour of the facility just over a week ago.

This summer saw global temperatures rising to the hottest on record, reaching 17.18 degrees Celsius, or 62.92 degrees Fahrenheit on July 4 – the hottest it has been in 125,000 years. And experts are predicting that the extreme temperatures are here to stay because of the warming effect of the El Niño weather phenomenon, coupled with increased carbon dioxide emissions from industry and human activities.

And with the record-high temperatures causing catastrophic consequences globally, the Barbados-based Caribbean Climate Outlook Forum (CariCOF) in August said that the Tropical Pacific and Atlantic Ocean temperatures should remain well above average over the next three-month period.

There are concerns that with so many schools having poor ventilation and cooling systems in the classrooms, students could face heat stress that may have dire consequences.

Some schools have begun to take precautionary measures while exploring resourceful ways to minimise the impact, but they fear it may not be enough.

Donald Quarrie’s vice principal said over the last two weeks they have been installing additional ceiling fans in classrooms in preparation for the new academic year, but he is less than optimistic about their effectiveness in keeping students cool and ready to learn under the prevailing conditions.

He noted that his school is on a shift system, and as such does not have the luxury of staggering certain classes in the mornings when it is likely to be cooler.

“The truth is, we are living in an era where climate change is really changing the landscape,” Williams told The Sunday Gleaner. “The heat that we are experiencing now in Jamaica, I am quite sure it will affect some of our students.”

According to Williams, students will also need to be educated on the impact rising temperatures can have on them and things they can do to help.

“Our dean of discipline may have some more work to do, our guidance counsellor may have some more work to do in terms of having sessions with them on how to manage the climate over which we have no control,” he said.

HEAT-INDUCED CLASSROOM DISRUPTIONS

With only one ceiling fan to a classroom of 38 to 40 students, acting principal at Mannings Hill Primary School, Audra Thomas-Golding, said heat-induced disruptions have become a common feature of the teaching and learning process.

“If the classroom is congested and the students feel bothersome, it means, therefore, that they are not going to focus on what it is that they are supposed to do. Persons want to exit from the classroom more than the regular time to go and refresh themselves,” Thomas-Golding explained to The Sunday Gleaner.

“We let them take their own water bottles, and so they are going to interrupt the lesson by going to their stations to take up water bottles, and even to take up the water bottles from where they are sitting.”

She envisions a day when each classroom at the St Andrew-based institution is equipped with an air conditioning unit. But for now, to aid the heat crisis, they will be hosting some classes outdoors under trees on the compound. A water cooler is also on the campus to help keep students hydrated.

BLOCK THE SUN FROM HITTING THE CONCRETE DIRECTLY

“I don’t know how some of these students study in some of these classrooms. They are furnaces!” declared architect and managing director at Cornerstone Design Ltd, Christopher Whyms-Stone.

He noted that a lot of the schools in Jamaica were built without fully taking into consideration the impact of climate change. But as school administrators mull on how to address the current heat crisis, a practical option, he said, is to clad walls with other materials such as wood to prevent the sun from hitting them directly.

Whyms-Stone contends that unless an effort is made to prevent the concrete surface from storing heat, then fans will be ineffective as they “might just be circulating that hot air that is in there”.

“The problem with concrete, in general, is that it is a heat battery so it stores the heat from the sun hitting it, literally like a battery, and lets it back out at a later time. That’s why the heat you feel is emanating from the walls inside the classroom. Same principle for the roof: if it’s a concrete roof, you have to do something to block the sun from hitting it,” he said.

“Depending on the school, a more architectural kind of intervention is to make bigger openings in the perimeter wall to make it as breathable as possible, so even on a still day there is still some amount of circulation.”

For schools that are now under construction, the architect suggests building ceilings at least 14 feet high, and placing louvre windows just underneath the ceiling’s highest point to help remove heat that comes into the space.

“Hot air rises, so in principle, the lower part of the classroom is cool because the hot air goes high,” he said. “By making the floor to ceiling higher and putting high windows just underneath the ceiling, that hot air moves out much faster. Naturally, you want windows at a lower level to bring breeze across the human scale – somebody standing or sitting in the classroom – but you need escape routes and quite sizeable ones for the hot air that sits in rooms.”

He lamented that most schools in Jamaica have a ceiling of nine feet high, so students are engulfed in hot air daily.

Whyms-Stone also suggested that schools plant trees around the compound to provide shade for both the students and the buildings to reduce the impact of the heat.

Tree planting was an initiative that principal of Kingston Technical High School, Maulton Campbell, embarked on a year ago.

“One of the things with Kingston Technical is that we have beautified the place and we have also been planting a lot of trees. We have been trying to green our school as much as possible because that is one of our visions,” he told The Sunday Gleaner.

Only some of the classrooms at the 127-year-old institution are equipped with a wall fan. Others rely on wind passing through the huge windows that remain open throughout the day. But with the in-land effect of the school’s location, that mode is unreliable.

Campbell’s dream is to one day install air conditioning units in all classrooms, powered by solar energy.

“We don’t have AC yet, but my dream is to have solar panels on all the blocks which can power the ACs,” he said.

TEACHERS HAVE TO MAKE ADJUSTMENTS

Child psychologist Dr Orlean Brown-Earle explained that excessive heat can increase aggressive behaviour in children, and they are more likely to be irritable as extreme heat disrupts the neurotransmitters in their brain, which affect how they think and behave.

“We have to remember that children are not mature individuals, so they are going to act out more than another individual will, and what will also happen is that this can lead to confusion and difficulty concentrating,” she explained.

This, she said, can result in poor performances on assessments. She stressed that teachers need to be cognisant of this and adjust how they relay lessons.

“We want teachers to understand that they can’t be running two-hour teaching sessions. They have to modulate and regulate the length of time per teaching session, give time to calm down and drink and stuff like that. So, for example, if it is really hot and you have a 40-minute lesson, it might just have to be a 30-minute lesson and ensure that the children are hydrated,” she said.

RECOMMENDATIONS TO NOT GET HEAT SICK

Medical doctor Garth Rattray said heat stress can also affect students physically.

“It can cause lethargy and dehydration. People can get sick from the heat, feel faint, and some people even stop sweating because they shut down so badly. They don’t sweat and that makes it worse because they can’t [release heat],” he explained to The Sunday Gleaner.

“When you sweat, what the water does is that it evaporates, and to do that, it takes the heat from you to evaporate, and if the body stops sweating because it is dehydrated, then that is just disastrous.”

He said there is also the possibility of students having heat strokes, but that is more likely to occur outside.

Rattray recommends that students be encouraged to stay hydrated throughout the day and wear cotton underneath their uniform. He is also advising school administrators to postpone physical education classes on very hot days and create as much space as possible between students in a classroom.

RENEWABLE ENERGY PILOT PROJECT

Cognisant of the impact the extreme heat will have on students, Minister of Education and Youth Fayval Williams said the ministry has contracted a company to pilot a renewable energy project in 30 schools. She said the initiative should have already started, but is hopeful that it will come to fruition this year.

“Once we are able to do that, we can see how we are able to provide air conditioning units or more fans in our schools for our students. But to do so now under the existing system, where we have to pay our power company for energy, it is gonna be just exorbitant. So we will see how that pilot project goes, then we will roll it out after that,” she told The Sunday Gleaner.