( Daily Mail ) Dr Suneel Kamath has noticed a ‘heartbreaking’ shift in his cancer clinic over the last decade.

As a gastrointestinal oncologist at the world-famous Cleveland Clinic, he was used to seeing colon cancer patients fit a similar mold: patients who are obese and in their 50s, 60s and beyond whose routine colonoscopies had come back abnormal.But in the last 10 years, he’s seen more and more patients in their 20s, 30s, and 40s.

He told DailyMail.com the harrowing reality of delivering a life-changing diagnosis to people getting ready to go back for another semester of college, in the midst of planning their weddings or getting ready have children.

And while several are part of the most vulnerable demographic – overweight, sedentary, black Americans – ‘plenty’ of patients work out most days and report eating plenty of veggies and fiber.

‘It definitely stands out to us that the age numbers are starting with twos, threes and fours so much more often than they did even just 10 years ago,’ he told DailyMail.com.

‘The conversations we’re having in the clinic are just heartbreaking.

‘That’s really the motivation for doing this research now. We have to figure out why this is happening so we can stop it.’

Dr Kamath works at Cleveland’s dedicated Center for Young-Onset Colorectal Cancer, which launched in 2021 to get to the bottom of the puzzling and terrifying rise in young people cancers.

His team’s latest breakthrough, published in a medical journal last month, appears to confirm that diets are to blame, rather than environmental factors.Dr Kamath’s latest study comes as more than 50,000 Americans are expected to die from colorectal cancer this year. And for young people, figures are expected to double between 2010 and 2030.

Some experts theorized that the explosion of colon cancers in young people may be linked to microplastics, other potentially carcinogenic chemicals or even gut issues caused by antibiotics or fungal infections. These factors were feared to disrupt our microbiomes, the complex network of bacteria in our stomachs.

But Dr Kamath’s team appears to rule those factors out.

They found that compounds linked to red and processed meats – like deli ham, hot dogs and burgers – are at much higher levels in young people with the disease, as opposed to a disrupted microbiome.

‘Researchers—ourselves included—have begun to focus on the gut microbiome as a primary contributor to colon cancer risk,’ the team wrote in the study, published in the journal NPJ Precision Oncology.

‘But our data clearly shows that the main driver is diet. We already know the main metabolites associated with young-onset risk, so we can now move our research forward in the correct direction.’

The research looked at 64 patients who had been diagnosed with colorectal cancer.

Just under a third were diagnosed before age 50, and 45 percent of young-onset cases were stage four, suggesting they had a delayed diagnosis. This is consistent with what Dr Kamath is seeing in his clinic. Increasingly, younger patients come in with later stages of disease, which he said could be because younger patients may have been more likely to ignore their symptoms.

Doctors may also be more likely to attribute them to more benign conditions like hemorrhoids.

Dr Kamath and his team collected samples of participants’ plasma, part of the blood that transports nutrients and maintains blood pressure and volume.

They found young patients had higher levels of metabolites created by the digestion of an amino acid called arginine.

They also have higher metabolite levels tied to protein digestion from meat.

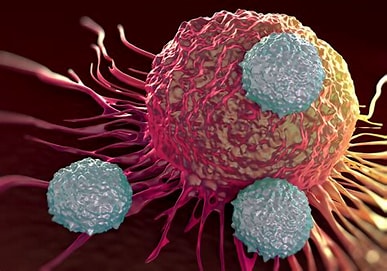

Dr Kamath believes the metabolites help feed cancer cells and ‘hijack’ normal cells.

This causes tumors to grow while depriving healthy cells of needed energy to sustain normal functions.

Why young people tend to have higher levels of the metabolites than older people with the same disease remains unknown.

Interactions between different factors, like when our gut bacteria consume our metabolites and produce their own, make the picture even more complex.

‘We’ve been putting a lot of effort into trying to figure out why this is happening and what’s different,’ Dr Kamath said.

Other recent research has suggested it is the consumption of processed meats that is the problem, finding that eating them more than once per week was associated with an increase risk of colon cancer markers.But while the team investigates these mechanisms further, Dr Kamath highlighted how lifestyle can play a major role in the development of colorectal cancer.

In Dr Kamath’s clinic, many of his young patients are either obese or spend most of their days sitting down, such as at an office job.

These two factors have been shown to increase insulin and other hormones in the blood, which could lead to cancer growth, as well as inflammation and increased metabolite levels.

‘About 70 percent of America is either overweight or obese, and that is happening earlier and earlier in life,’ he said.

‘We’re seeing teenagers and kids that are eight, nine and 10 years old that are significantly overweight. The weight issue we have the in the United States also plays into this.’

There were limitations to the research.

Mainly, the team is still unsure why so many patients like Dr Kamath’s are getting colon cancer despite eating little to no meat and maintaining a healthy lifestyle. For some patients, this may be due to genetic mutations.

According to the National Cancer Institute, these mutations can change how certain proteins function in the body, which could lead to cancer cells forming.

Dr Kamath noted that these changes are more common in older patients, as protective cells begin to deteriorate. When cells break down, they are more vulnerable to mutations.

Though he notes that younger people may be better protected against these genetic changes, as their cells are healthier and more protective, it’s still possible that they could suffer cancer-causing mutations, despite a healthy diet or lifestyle. laming burgers, sausage, and bacon, as well as obesity, isn’t new, as evidence against these risk factors has mounted in the last few years.

However, what’s unique about the study is how it detected markers of colorectal cancer.

Dr Kamath’s team measured metabolites with metabolomics testing, a simple blood test that can be performed on samples even decades old, provided they are properly frozen and stored.

‘This is really just simple blood draws, so that’s another attractive aspect of this test,’ he said.

In addition to blood, metabolites can also be detected in urine. If levels appear high, it could indicate that cancer is growing somewhere in the body.

This type of testing isn’t used in the clinical space yet, but Dr Kamath said that with future studies, it could become an early screening too for colorectal cancer.

And when it eventually does, it would likely cost under $200 before insurance.

‘The next step would be to do a colonoscopy to look for where the cancer is located.

‘But this test could be a way to prompt us to do so for someone that would not have otherwise needed a colonoscopy,’ he said.

‘The work we’re doing is leading to that.’

But even as Dr Kamath’s patients gradually become younger, he said his research shows that colorectal cancer could be prevented before it starts.

While recent research has pointed to the gut microbiome – a complex network of bacteria that regulates digestive and immune health – as a driver of colorectal cancer, it can be influenced by a number of factors like medications and environment.

This can make it more difficult change, whereas dietary changes like lowering red and processed meat consumption could be more attainable.

And the younger generations may be taking note. Research from Tulane University suggests that Boomers are responsible for most of America’s red meat consumption, and overall consumption has dropped about six percent in the last two years.

More research is still needed, but Dr Kamath believes that it’s a step in the right direction for keeping more young patients out of his clinic. ‘It gives us something we can actually counsel patients about in the clinic,’ he said.