The head of the Pan-American Health Organisation (PAHO) has endorsed Barbados’ National School Nutrition Policy and urged authorities to maintain it to help rein in obesity and other health issues among children.

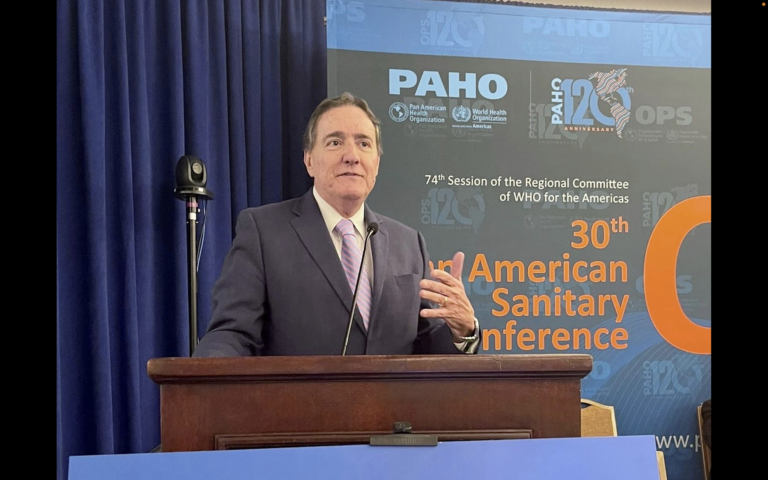

At the same time, PAHO Director Dr Jarbas Barbosa advised authorities to pair enforcement with education to get students’ buy-in as well.

Supporting the concept of the National School Nutrition Policy as a measure to help combat the noncommunicable disease (NCD) crisis, he said he has seen similar measures work in other jurisdictions.

“In some countries that adopted ten years ago, 15 years ago, [similar] policies in schools, they stopped the increase of the overweight and obesity [in children] and [saw] a decline. What is very well established [around] the world is that children in their adolescence are a very important group to provide not only information but you need to support behavioural change. [If] the canteens are offering only unhealthy foods, probably these children will be used to that [and] will not develop a taste for fruits, vegetables and other things,” he said during a press briefing at PAHO headquarters, on his first official visit to the island.

His encouragement to authorities to continue on the current track comes as some members of the public question the policy which is aimed at ensuring that only nutritious foods and beverages that enhance the health, learning and well-being of school children are sold, served and promoted in school environments.

Under the policy which took effect in April, only low-sodium snacks and snacks with no more than 25 grammes of total sugars and three grammes of total fat per serving are allowed on school premises. Snacks containing three grammes or more of fibre per serving are on the approved list, as well as snacks low in cholesterol – 40 milligrammes or less per serving.

Beverages allowed are options with no added sugar, 100 per cent juice, water, non-sugar-flavoured water, 100 per cent vegetable juice, 100 per cent fruit juice, coconut water, sparkling water, reduced-fat milk, and unsweetened hemp milk.

Teachers are expected to monitor what students bring to school to ensure they comply with the nutrition policy.

Though Dr Barbosa admitted that he was not aware of all the specifics of the new policy, he stressed that given the explosion in the number of children being recorded as obese or with an NCD, such initiatives will be critical in addressing the problem.

At the same time, he stressed that countries like Barbados should not focus solely on the enforcement of such policies, as education and access to important information play a critical role in addressing health needs.

“Sometimes we have a lot of discussions about enforcement versus information…. Children sometimes like to challenge things. They are not allowed to do something [but] they want to do it . . . . A good combination of information [and] engagement to tell them why they need to eat in a healthier way, I think that is better,” he said.

“We [should] start in the schools; provide information to them, encourage them to eat healthier foods. I think that is a very important step to reduce obesity, because when we talk about overweight and obesity, we are not only talking about the adults, but we have in some countries 30 per cent of the children that are overweight and or obese.”

Even so, Dr Barbosa, who is also Regional Director of the World Health Organization (WHO), emphasised that such policies alone will not be the answer to the NCD pandemic in the region.

He said more has to be done to monitor and diagnose diseases at the earliest possible age.

“One of the priorities that I have mandated is exactly how we can renew and strengthen primary health care to provide proper diagnostic treatment for diabetes, hypertension, cancers and other diseases,” Dr Barbosa said.